Cache · Billytown · 2023

Cache

25.11.23–13.01.24

Duo with Christofer Degrér, Billytown, The Hague NL

“The apartment was a box I had been hidden in, or maybe a book I had been written into. Outside was no different, words fell, soaked into the ground, and were stored there indefinitely (...)” Featuring works by Maja Klaassens and Christofer Degrér, Cache is a duo exhibition which reflects on the technology of writing, and explores the impact of literature and film on perceptions of domestic and natural environments.

Cache

Angela M. Bartholomew

As an art historian, I experience the past as a reservoir, an endless resource to reframe the present. In reflecting on Cache – Maja Klaassens’ and Christofer Degrér’s duo exhibition at Billytown – my mind goes to another exhibition that occurred precisely thirty years ago. The Sublime Void: On the Memory of the Imagination (1993) took place at the Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, with its central theme “the interweaving of memory and imagination in the artistic process.” Curator Bart Cassiman conceived of the structure of the exhibition as a poem, the works functioning as words, showing “different facets of themselves” dependent on the order, combination, or context in which they are read. While art historical tradition played a key role in his selection of works, Cassiman was interested in historical inference as an implicit force, asserting that history involves forgetting, and is fundamentally creative in nature. Memory, he wrote, “preserves the past in the stratification of its multiple layers and its essential irretrievability.”

With this in mind, The Sublime Void resonates thematically and aesthetically with Cache. Both exhibitions elicit thoughts about memory, historical tradition, and hidden places. Artists such as Lili Dujourie, Niek Kemps, Luciano Fabro, Rachel Whiteread, and Fortuyn/O’Brien demonstrated a fascination with materials and their transformations: Dujourie’s use of mirrored mirrors, Kemps’ polished reflective surfaces, Fabro’s fixation with the surface as a shell (a metaphor for the encompassing viewing apparatus), Whiteread’s casts of domestic forms – they all reverberate with tendencies in the practices of Klaassens and Degrér. The need to explore the reality of illusion is demonstrable for each of these artists, a desire felt to capture something real through the production of the artificial.

With Fortuyn/O’Brien there is a special connection: working as one, the artists produced what they referred to as ‘domestic sculpture’. Lounge chairs of Carrara marble, carpets rolled in diagonal division, ovular mirrors nesting in freestanding pedestals. These sculptures were utilitarian in design but too fragile to be functional, in colors or transparencies that deny their material. In their installation, sculptures were placed in relation to one another, often in pairs, and relative to surrounding architectural elements and fragments of décor. They evoke a sense of theatricality, as if the visitor is interrupting a scene. In Cache, Klaassens and Degrér likewise work together to create a scene from an otherworldly, but vaguely familiar domestic space. The scene takes shape from a collaboratively written account of its inhabitants, yet this text remains concealed to its visitors. As we step into a fragmented apartment, doors become windows, and interior and exterior worlds merge.

Distinct from The Sublime Void is the sense of foreboding in Cache that emerges from what we often call ‘nature’. As the results of violence wrought on our environment materializes in myriad ways across our planet, we are confronted with the utter falseness of a nature-culture dichotomy. While in the eighteenth century, the concept of the sublime was applied to aspects of nature that generate awe, such as stormy seas or the vastness of an abyss, today it might be associated with the scale and speed of destruction, or the seeming limitlessness with which growth and convenience has infected our existence. In Cache, the experience of nature itself as unnatural is conveyed in palpable ways. Walking past the meadow of Degrér’s hyper-green chroma-key weeds, we are surrounded by an undead accumulation. Each plant has been sourced from liminal spaces of human development yet-to-come or left fallow. Caked in polymer-based paint, the flora is plucked from one context, restaged as a field of greenscreen green. In another scene, this green has spread to a single rose, riddled with thorns removed by the artist from wild roses only to be reattached with surgical tweezers. With the rose, real and synthetic come together, a tendency found in the work of both Degrér and Klaassens.

Turning the corner, the sharp lines of Klaassens’ Tributyltin cut through the space of the gallery. Coated in glossy black, the four-meter long kayak glides along, emanating a sense of indifference not unlike that of a sea mammal. Small barnacles and starfish, sculpted from epoxy clay, have become one with the vessel. There is a suggestion evident that we encounter this biotope, a fusion of object and organism, after its complete submersion in crude oil. Viewed in combination (or agitation) with the architecture of the white cube, associations regarding the complicity of the corporatized cultural industry in the proliferation of the oil industry rise to the surface. The title of the work points to a contaminant, Tributyltin (TBT), a biocide used in paint to repel barnacles and other organisms from ships and marine infrastructure. TBT has been directly linked to endocrine disorders in marine life and humans, and while banned in 2008, the chemical compound continues to accumulate on the ocean floor and contaminate water supply. Thus, nature made unnatural impinges upon our physical autonomy. It infects our bodies precisely because we are not, and have never been, distinct from the environments we inhabit.

Narratives about nature are rife in an exhibition about the malleability of memory, of the role of fragments in storing the past, of ghostly apparitions that materialize in the writing of our present. Cache shows us that there is memory in material, and that memories can be material themselves. If remembering is a form of writing, an exercise in borrowing and reframing material, it can be both a dangerous weapon and a saving grace.

Angela M. Bartholomew is assistant professor of modern and contemporary art history at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. She researches, writes, and teaches on the myriad forces that shape the production and presentation of art.

Kindly supported by Gemeente Den Haag · Mondriaan Fonds · Helge Ax:son Johnsons stiftelse

Photography · Jhoeko

← Swipe for more →

A Line of Stones · Dürst Britt & Mayhew · 2025

A Line of Stones

18.04.25 - 08.06.25

Dürst Britt & Mayhew is proud to present 'A Line of Stones' by Maja Klaassens. After her presentation in the Frontspace in 2022 this is the first exhibition since the gallery started representing her in 2024.

In her new body of work, Maja Klaassens explores the function of editing in literature and film, and the ways it influences our perception of the world around us. Drawing from numerous works of fiction, the exhibition posits the everyday as a stage upon which fragmented and incomplete narratives generate suspense.

Focussing on the ways domestic and natural environments are often written in opposition to one another, neutralizing and shaping both, Maja Klaassens' works consider the traces which collapse these thresholds. A simple impulse like pocketing a stone at the beach can expand in all directions: repeatedly re-written, re-made, and re-framed by the artist in a variety of mediums, each adjustment revealing layers of underlying tension.

Two distinct series of works will be on show. 'Washing' consists of personal and found textiles, which are meticulously folded into rectangular wooden boxes. 'Nightstand' is a series of seven lifelike nightstands, filled with objects, and completely constructed as if carved from stone. These two series of works are partnered with 'A Line of Stones', Klaassens' new video work, which is a mesmerising mix of roadmovie, poetic narrative and soundscape.

The exhibition is accompanied by a specially commissioned essay by writer Martijn Simons, which you can read here.

Photography: Gert Jan van Rooij

← Swipe for more →

After Daan van Golden · Parts Project · 2021

After Daan van Golden

05.09.21 - 07.11.21

Parts Project, The Hague NL

With: Daan van Golden, Richard Aldrich, Ronald de Bloeme, Carel Blotkamp, Indigo Deijmann, Maurice van Es, Fergus Feehily, Kees Goudzwaard, Mirthe Klück, Niek Hendrix, Robbin Heyker, Maja Klaassens, Marijn van Kreij, Just Quist, Magali Reus, Julian Sirre, Annemarie Slobbe, Alice Tippit, Riëtte Wanders.

Curated by Niek Hendrix and Robbin Heyker.

Photography: Jhoeko

← Swipe for more →

Wall mount for Eternity Moment by Calvin Klein · 2022

Photography: Katherina Heil

← Swipe for more →

Narcissus Poeticus · 2019

Exhibited within the solo exhibition of Bernice Nauta: Hello Echo, 2019, 1646, The Hague NL

← Swipe for more →

Maja Klaassens · the Kitchen · 2015

Maja Klaassens at Billytown the Kitchen

2015

Billytown, The Hague NL

Photography: Jhoeko

← Swipe for more →

Mountain Friends · Fred & Ferry Gallery · 2024

Mountain Friends

13.01.24 - 10.02.24

Fred & Ferry Gallery, Antwerp BE

A group exhibition initiated by Mirthe Klück at Fred & Ferry Gallery, Antwerp (BE) with Kaï-Chun Chang, Daniele Formica, Maja Klaassens, Nishiko and Mirthe Klück.

Photography: shivadas

← Swipe for more →

Orca · Dürst Britt & Mayhew · 2022

Orca

19.03.22 - 8.05.22

Dürst Britt & Mayhew Frontspace, The Hague NL

For her exhibition ‘Orca’ Maja Klaassens brings together a body of work consisting of painting, sculpture and installation. All works testify of the ephemeral nature of memory and the human desire to collect, record and store our memories.

Klaassens explores the way we isolate, edit, re-arrange, and save images and objects. These fragments become props in semi-fictional or metafictional texts we ‘write’ in our own mind, as a response to experience and reality.

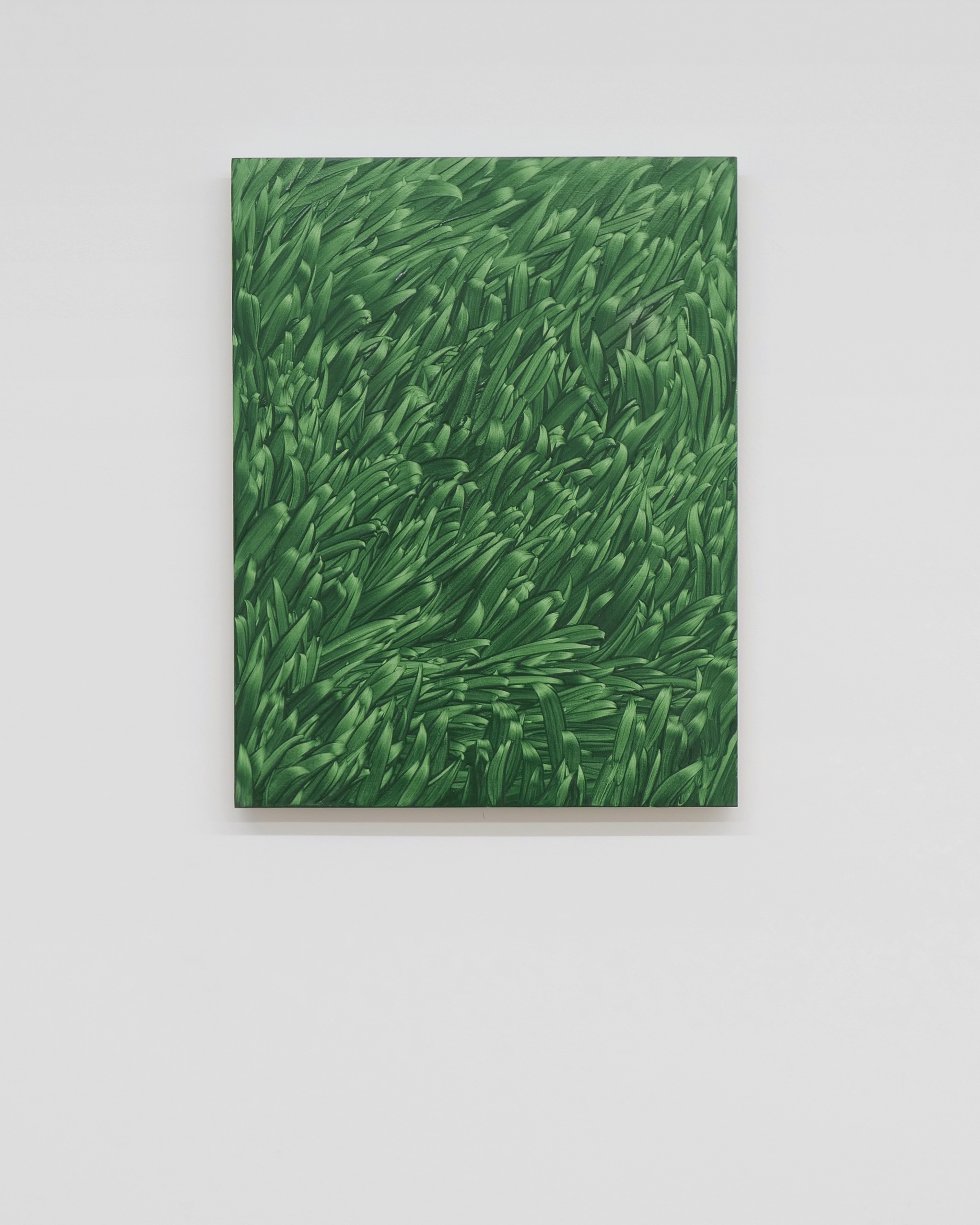

Her interest in writing as an internal mechanism reveals itself within the works in the show. Klaassens’ ‘grass’ paintings have been executed as if writing, concentrated at a desk; rose thorns on branches can be read like words on a line, and strips cut from a photograph of an orca fin are readable as both individual lines and a whole image.

Thorns and an orca fin can act as both a fragment and a pars pro toto, as what is missing continues to exist as a ghost. To Klaassens, this reflects how experiences remain behind the fragments we extract from them and form into memories.

A black fin on a black reflective dinner table turns the surface of the table into the surface of the ocean. Resembling a large screen, the table becomes the bottomless pit of the interface. The impression is uncanny, and encourages the viewer to fixate on the details of real and fabricated elements within one work.

The similar shape of the thorn and the fin emphasises the way threats and protection can occur together. Klaassens tries to find ways to show how recording memory can be both pleasant and anxious: leaving us questioning the missing parts of what happened in the grass, or at the dinner table.

Dear Maja,

I remember when we first met, the way we bonded over the bizarre parallels in our upbringings. Despite coming into the world on opposite sides (you, in Nelson, and me, in Toronto), we share so many of the same experiences and internalized values. Growing up in two settler-colonial limbs of an empire that stretched itself from your corner of the planet all the way to mine, as schoolchildren we’d learned a manicured truth. We each remember taking field trips to pioneer villages where we were taught a version of history absent of violence. We learned handicrafts in our day programs, where lessons emphasized the technical aspects but minimized where they came from.

It’s funny, before we met I was never confident in my memories of growing up. Apart from a few major family events, nothing stuck out. It’s as though the older you get, the more stubborn the subconscious becomes, whittling away at the past to form a discernable shape, regardless of whether or not the shape is accurate. I suspect this is a symptom of the world we live in, where the past is constantly glorified as a “simpler time,” being flattened, condensed, and summarized into something much smaller than what it actually was or felt like. It doesn’t help that my perception of time and attention span have been irreversibly altered thanks to how much time I’ve spent behind screens (embarrassing).

What I mean is that memory can be hard to locate, and when we do find it, it’s almost impossible to understand how it’s being distorted by the present. I think this is why I was so taken by the grass paintings the first time I saw them. Monochromatic scenes depicting the texture of a patch of grass recently subjected to an encounter. Impressed upon by lovers, or a struggle, the grass is a witness to an event that is familiar, but also inaccessible. Placeless, and in the paramount of its growth, the grass in these paintings clings to a feeling rather than a date. Like the amygdala, they’re unbothered by logic or specifics. Inscribed in your grasses are charged moments, documented by microscopic brushstrokes, which, fittingly, are made by gestures you compare to handwriting.

The ambiguity I sense from the grass paintings is akin to how I feel when trying to access parts of my past. It’s an embodied nostalgia built up of dread and intense longing, but also of idealism. For me, your recent work addresses this dissonance, this unruly knot of reality and fantasy that we call memory. When I think of the grass works, what surfaces is always slightly different. My responses are filtered through the sediment of today: what I ate for breakfast (eggs), how I slept (poorly), the way the grass looks here and now (a pale, Wintery yellow). In any case, I suppose the point is that anything surfaces at all, the tip of the iceberg, so to speak. Or, the fin of the orca. Like a flashback or reflex, it’s a smaller fragment attesting to something beautiful, wild, but never completely available.

I didn’t grow up around orcas like you did, but I think I understand why they come up in your work. There is something tragic, as well as ironic, about a killer whale being endangered: to think that one day the entire species could become a distant memory. Echoing the waves, the simple, somewhat alien, shape of a dorsal fin evokes so many visceral reactions in people. There’s a curiosity to see what it’s attached to, but also a fear of finding out and being consumed. Cutting through water like a blade, the fin somehow casts the ocean’s vastness into scale. Disembodied by the water level, the fin takes on a different meaning, emphasizing what can’t be seen. The detached form carries a symbolic threat, reminiscent of other alleged predators, like its cousins the shark fin, the cat claw, and, remarkably, the rose thorn.

I remember the first time I visited your studio, you showed me one of your rose thorns. It was tiny, and impossibly sharp. The gradient from the base to the tip suggested it had just been trimmed from a stem, freshly removed from its context. While I hadn’t seen a rose thorn up close in years, the detail was uncanny, I felt the baseline tingle of a subtle threat. The act of trimming carries a kind of banal violence. For florists and gardeners, I imagine it’s a daily practice. All for the sake of a full vase on the counter or a corny romantic gesture (the domination of plants and animals is an eerie second nature). Your severed thorns and stems never fail to remind me of that. That is, of the casual violence that happens in the background of our daily lives.

Growing up, my grandmother had a rose bush in her backyard that bloomed every spring. Again, there are seldom discrete moments I recall from childhood, but the smell of blooming roses delivers me to a certain state of being. Of feeling small and safe, with crisp air in my lungs. I don’t return to an isolated moment, but an accumulation of them. Like a bouquet, or waves lapping into the shoreline, there’s a potency in volume that overpowers a singular event. I think there’s something about your practice that operates in a similar way. In your work I sense a tendency towards an accumulation of thought, repetitive gesture, recognition. A form of déjà vu that works somatically. Have you ever had that kind of déjà vu? It’s a simple fact that no moment can happen twice, though sometimes we don’t want to believe it.

You described your latest table work as born from a compulsion to retain certain experiences through the preservation of their parts. It’s a casual dinner scene, encased by a black reflective layer. A relic of togetherness, with all the fixtures of a perfect date: a great meal and drinks spread out on a surface that looks like it could go on forever. It’s a perfectly orchestrated account of a fleeting moment, but too good to be true. Like other distant memories, some details have vanished, while others spring up. There’s no place for scraps or imperfections, leaving behind a streamlined account of things. What was once improvisational is now refinished, rewritten, cut down, perfected. There's something impressive, and violent, about how we buff out certain details, becoming the authors of our own remembrance.

It’s been a pleasure to watch these new works come together, hope to see you again soon.

Always,

Danica

Danica Pinteric (b. 1994) is a curator, writer, and editor based in Tkaronto/Toronto, Canada working from an ethos of care, collaboration, and sustainability. Her writing has recently been featured by DRAC (Drummondville, QC), Stedelijk Studies (Amsterdam, NL), BAD WATER (Knoxville, TN), Nanaimo Ceramic Arts (Nanaimo, BC), Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam, NL) and Laurel Projects (Amsterdam, NL). She holds an MA in Curating Arts & Cultures from the University of Amsterdam, and a BA in Communications & Cultural Studies from Concordia University. She is the founding director of Joys, an independent platform for contemporary art based in Toronto.

Photography: Gert Jan van Rooij

← Swipe for more →

Rose · 2022

Rose, 2022, ongoing series

Photography: Gert Jan van Rooij

← Swipe for more →

Grass · 2022

← Swipe for more →

Hinkypunk · Billytown · 2019

Hinkypunk

29.11.19 - 01.02.20

Billytown, The Hague NL

This exhibition is a collective project by Anders Dickson, Maja Klaassens, Clémence de La Tour du Pin, and Kim David Bots. Over the course of a two week period, an amalgamation of different material comes together in an installation focusing on the multi-layered notion of the swamp. Hinkypunk, a colloquial term originating in Somerset, England, refers to the mysterious lights seen in swamps that appear as a result of gasses spontaneously combusting.

Photography: Jhoeko and Kim David Bots

← Swipe for more →

Niek Kemps and Maja Klaassens · lxhxb · 2024

Niek Kemps and Maja Klaassens

20.4.2024 – 18.5.2024

Duo with Niek Kemps, lxhxb, Eindhoven NL

Sometimes you encounter an artwork for the first time and it’s puzzling and difficult to place. You understand that something is happening, but it’s hard to say exactly what. In the case of Niek Kemps I know this is a deliberate choice. He starts from a clear idea, which is then worked, wrought, and pushed until it becomes an untouchable superlative, standing alone in its own bit of universe. Kemps doesn’t mind if the audience is unable to trace where his thoughts originated. In fact, he likes it that way.

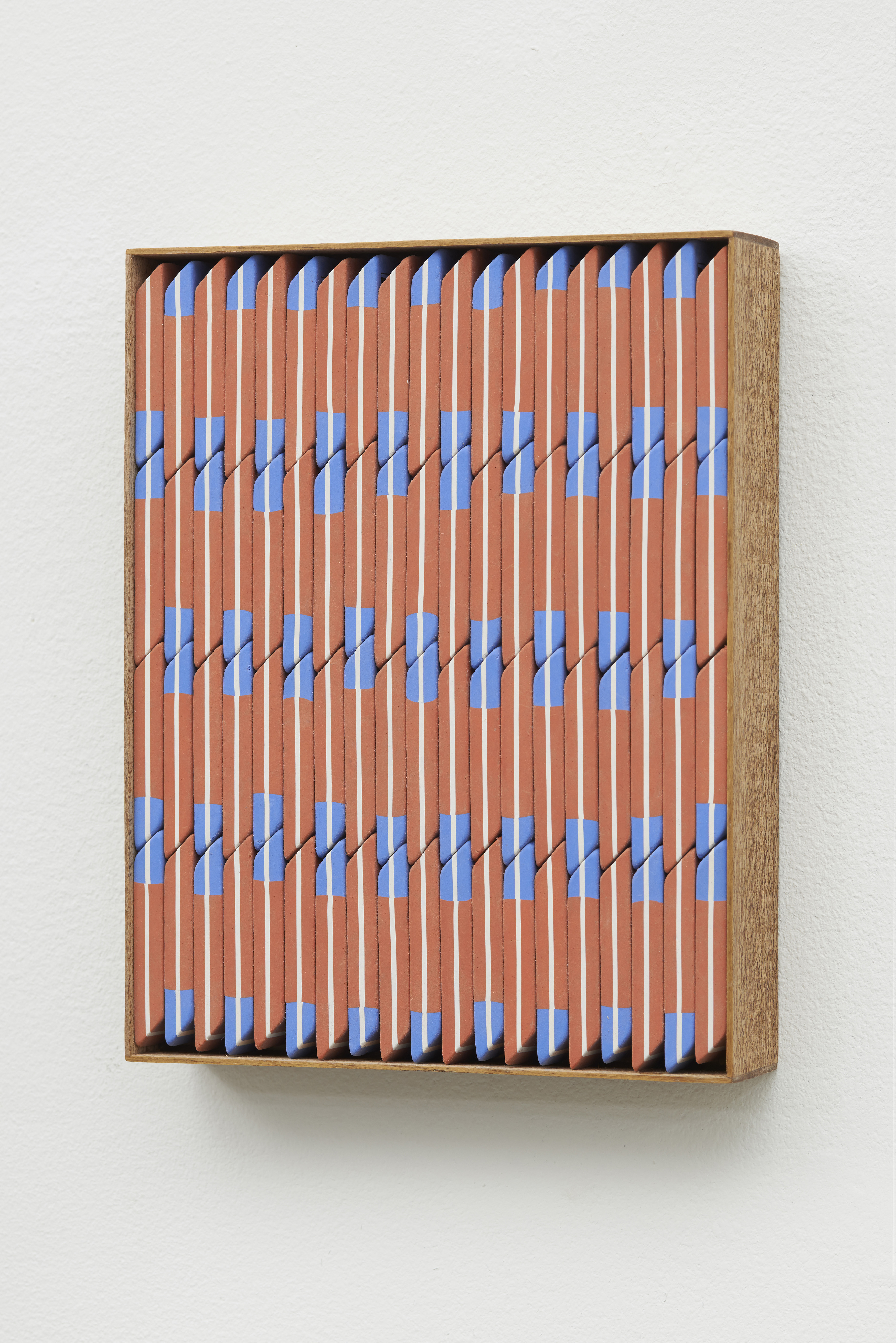

The work of Maja Klaassens is equally enigmatic, though through a different mechanism. Her works are often small in size, with everything being exactly measured, considered and deliberate. This much has been clear to me from the beginning. Exactly why it was considered and what was deliberated was nevertheless a mystery. A mystery that intrigued me then and has kept intriguing me since. In this exhibition some paintings that Maja straightforwardly calls Grass are combined with some works by Niek titled The Phenomenon of Preferred Spin Direction. Both works are complex constellations that through their parts form a new whole. In the case of Maja, the parts are only recognizable through the place they take in the whole, while for Niek the individual parts are discarded so that the whole can become a new entity. In their solemn silence both artists lie in each other’s extension, while through the details it can be gleaned that their approach is fundamentally different.

Photography · Guus van der Velden

← Swipe for more →

The view is total sea · Joys · 2023

The view is total sea

13.05.23 - 24.06.23

Joys, Toronto CA

For several years, or maybe her whole life, Maja has been followed by a recurring shape. The dorsal fin, the rose’s thorn, a tooth, a talon, the perfect ocean wave. A triangle with a curved tip; the queering of the strongest shape. For Maja this shape is both abundant and regenerative, though it typically appears as a sliver or a fragment removed from a greater whole. The acts of severance following this form are as mundane as they are violent, illuminating the moral implication of editing as an inevitable process of reduction.

Maja’s work is determined by an obsessive, cyclical archaeology of narrative structure. Across painting, sculpture, installation and lens-based media, she breaks down conventions from novels, films, and online spaces to reveal their function in how we interpret the everyday. Appropriating their techniques, Maja fragments, conceals, enhances, and repeats elements to influence their emotional register. Borrowing from several genres, her work carries multiple valences of meaning and addresses the tensions between opposing forces — romance vs. violence, indoor vs. outdoor, toxicity vs. purity, ephemerality vs. permanence.

Editing is a process of manipulation that advances the process of narrativization. It is an act of distillation – filtering an experience through the sediment of external influences and interpretation, producing a definitive version of events. Through her deeply technical and meditative craftsmanship, Maja constructs an enhanced, edited reality. Her work addresses real places and memories and then casts a veil over them — at best an act of preservation, and at worst, of neutralization. She disguises key referents, perhaps in observation of our collective willingness to lean into fantasy when it offers comfort or protection. Delusion is ultimately a protective reflex.

Maja’s perennial interest in the Gothic genre is palpable in works like Thorn and Little Saga (2023). Thorn is a recurring series of hyper-realistic, disembodied rose thorns. Lifted from their original context, they function as a fluid metaphor for both romance and protection, departing from literary tropes of innocence and purity into something more sinister. The thorns travel freely throughout the spaces they inhabit, finding their own place as weeds do in a garden, posing a small threat while exposing themselves to the risk of being plucked. Little Saga, a photograph of a found “castle by the sea” resembling an old ruin, signifies an ephemeral moment, a fleeting fantasy held by its creator before being abandoned. Like much of Maja's work, Little Saga and Thorn oscillate between indoors and outdoors, emphasizing the lineages of storytelling inherent to the domestic sphere.

The Sea, the Sea and Night Light (both 2023) use different materials but stem from the same line of research into ocean pollution. Using both manmade and luxury items, a designer faucet and an oyster shell, Maja considers the invisible threat of water contamination. The ocean is the vessel through which both items become valued commodity goods. Maja’s interest in Tributyltin (TBT) contamination underpins these sculptures, pointing to the politics of land stewardship and the governance of borderless waters. At once an ominous threat and essential resource, the ocean is itself a vulnerable entity.

Villette (2023), Maja’s debut with video, features an infinite loop of waterfront footage. Villette plays with the format of relaxation videos popular on YouTube — an endless stream of nature content intended to lull its viewers while they Relax, Meditate, Work, or Study. Villette fills the gallery with layered nature soundscapes recorded by and sourced online by the artist, another editorial tactic emphasizing the ways we cultivate our everyday environments. Villette is a simulation of place, raising the question of how we consume nature as a commodity or infinite resource. In subtitled narration, an unidentified protagonist retells an encounter with orcas in a sea cave, a linear tale embedded into a video which appears to otherwise resemble infinity. The work’s suspense could be easily missed, slipping between the cracks as audiences close their eyes and soften their focus.

On first impression, the works presented appear independent. It is only after some time spent with them that their connections begin to surface, the silent conversations they are having through the walls. They demand sensitivity and sustained attention before letting themselves be known, a kind of hermeneutic foreplay. Their uncanny, prop-like quality is a testament to Maja’s precise eye and her understanding that the objects we hold close are key determinants of the plot.

Danica Pinteric, May 2023

Presented as part of of Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival 2023 Core Program with generous support from the Consulate General of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Toronto.

Photography: Laura Findlay

← Swipe for more →

Clementina · 2022

← Swipe for more →